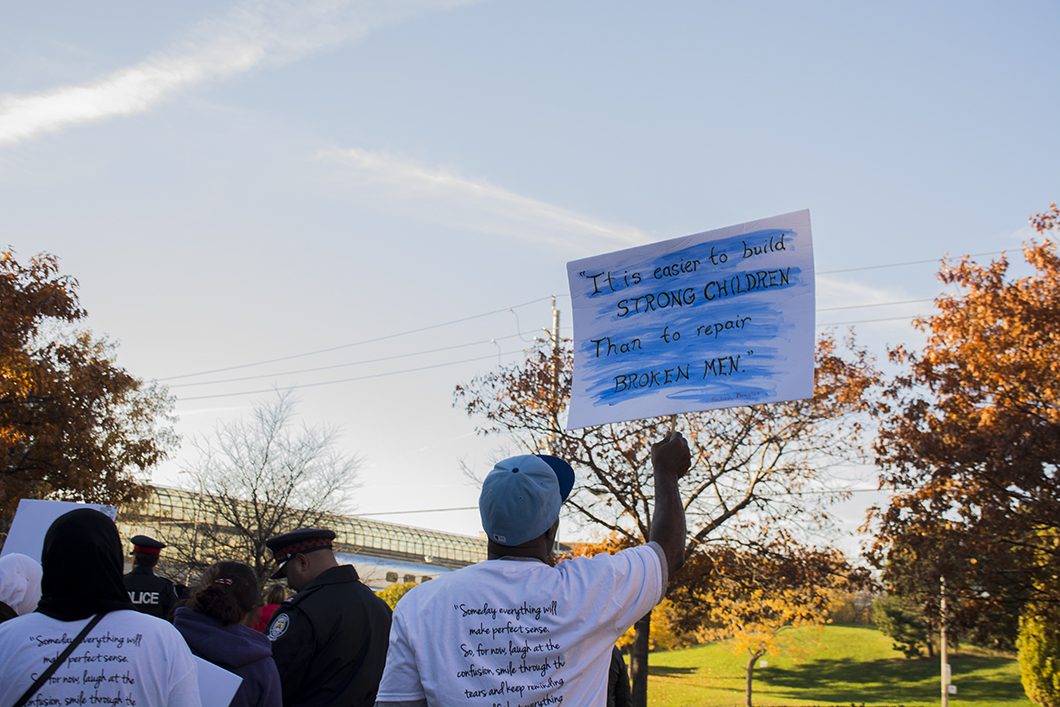

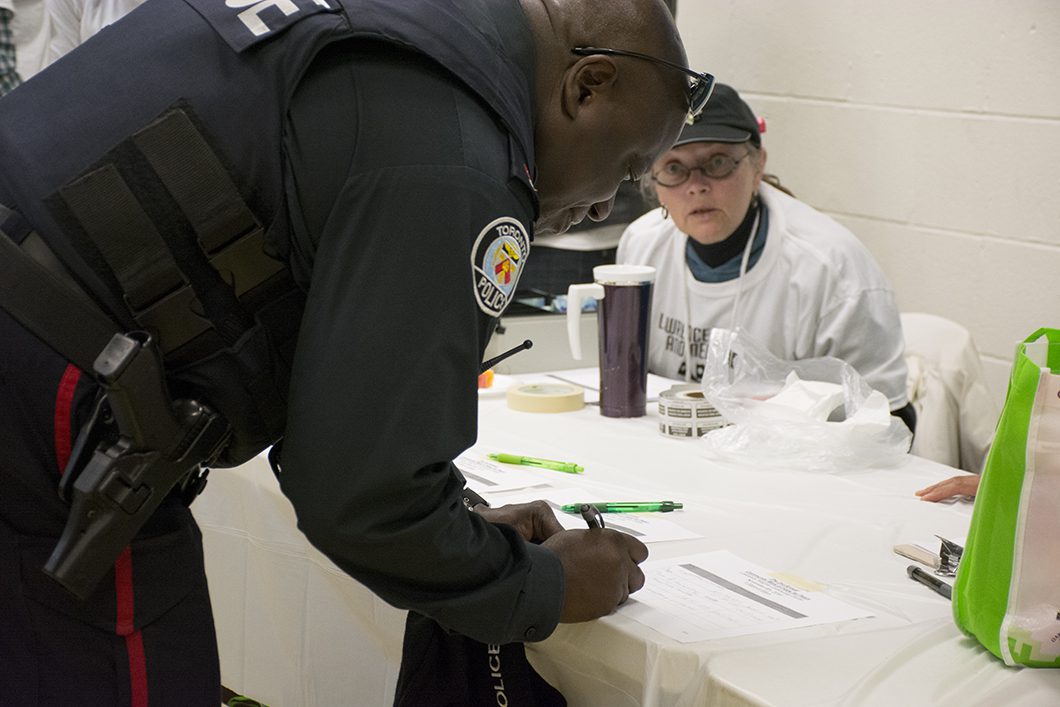

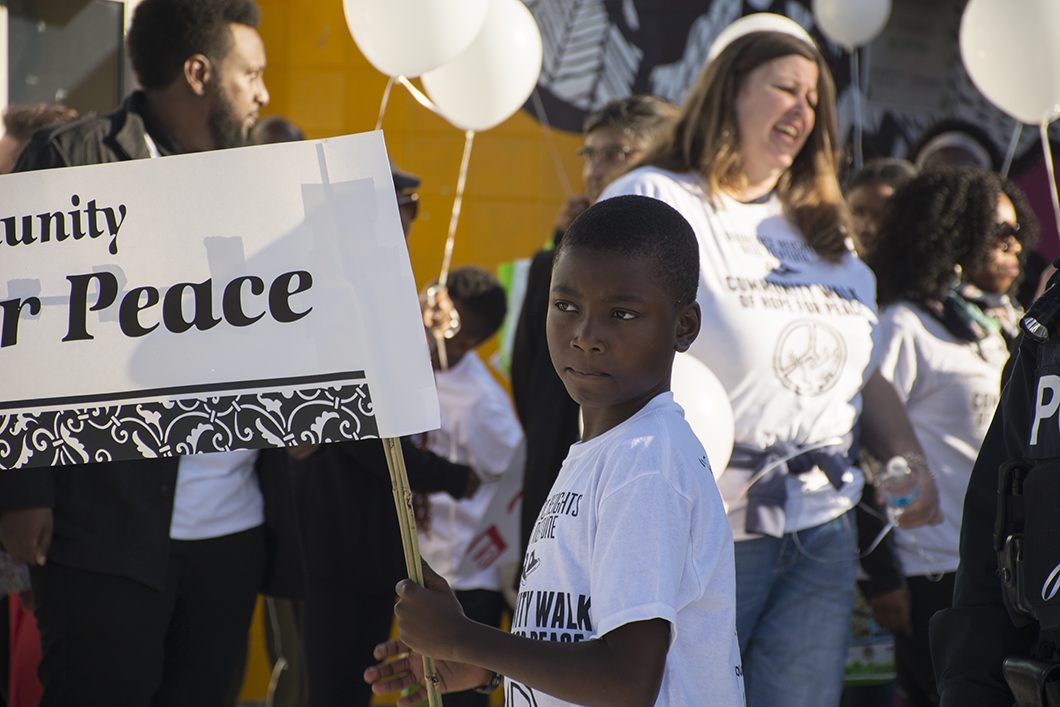

Winding through the streets of their north Toronto suburb, a group of about 100 demonstrators makes their way through Lawrence Heights and Neptune – a community within the Lawrence Heights neighbourhood. It was Nov. 6, 2016. There’s a quiet resilience amongst the crowd as they hold signs in memory of those they have lost to gun violence.

Their message is simple. It’s time for peace in the community that has felt the devastating impact of gun violence.

The walk began two years ago in memory of Abshir Hassan, a popular school teacher who was shot and killed in 2014. Hassan was not affiliated with any gangs in the area. He was killed by stray bullets while moving his car. Since then, the walk has grown to include all of those in the two communities who have been touched by gun violence.

Locals have called the Lawrence Heights area the “The Jungle.” The reputation is largely due to the fact that the area has been known to be a home to drug dealers, those living in poverty and gun violence. Lawrence Heights is one of the largest community housing projects in Toronto, and is currently undergoing a revitalization process.

Yet, despite the violence that is so common to the area, there’s still a real sense of community. Multiple times, one or two marchers divert from the walk to linger at the end of the yard of a friend or neighbour. Children playing in the yard call out to their friends who they see walking past them. The demonstrators want a place that is already rich with community, to be a safer place. They want better for the place they call home.

The neighbourhood is home to a large number of immigrants. According to a study by the City of Toronto, 51 per cent of the residents are foreign-born. The two largest ethnic groups are African Canadians (38 per cent) and Filipinos (35 per cent), followed by Eastern European (17 per cent). The other 10 per cent is a mixture of Middle-Eastern, South American and other groups.

Karen Tysdale has been a community advocate in the Neptune area for over 30 years. When a gun goes off, its impact extends far beyond the 911 call and the people involved. Communities feel the shock.

“(Gun violence) has caused fear for adults,” Tysdale said. “When there’s programming in the community they want escorts for their children to come from wherever they are to wherever they are going, like from home to the community centre…Parents want to make sure their children are escorted, for their safety.”

Their appeal comes as the city of Toronto has seen a 35 per cent increase in gun violence from 2016 over the year before. According to figures released by the Toronto Police Service, in 2015, there were a reported 414 victims of gun violence. In 2016, there were over 513. That’s an increase of 35 per cent. Homicides in Toronto were also being primarily perpetrated with guns. There have been 64 homicides in 2016; more than half of them (57.8 per cent), or 37, were as a result of guns.

Sarah Samwel/Toronto Observer

In May 2016, Candice Rochelle Bobb, a mother-to-be, was shot and killed while driving home through Jamestown. Police state that she was simply collateral damage amid this gang-related incident within the Jamestown communities. Bobb’s death shocked Torontonians and caused the media to descend in force, calling for change. Yet for many residents of the Rexdale area, this was just a recurring problem for which there seems to be no solution.

Pastor Sam Aragones of the Rexdale Aalliance Church has been working in and with the community and their youth for 18 years. He has his work cut out for him tackling gun violence.

“There was a real sense of hopelessness and helplessness [after the death of Bobb],” Aragones said.

Aragones hosts many organizations and events at his church to try and give the youth of the community a place to turn besides gangs.

“There are generations of kids who grow up without seeing anyone go to work. These kids, they see joining a gang as a way to make money quickly, to break the cycle of poverty,” Aragones said.

According to Aragones and other outreach workers based out of the Rexdale Alliance Church, the root cause of gangs is poverty.

“We have a porous border with the United States. The guns will keep coming in somehow,” the pastor said. He goes on to say that if the many facets of poverty are addressed, the need for guns and people willing to use them will decrease.

“People join gangs because they have limited to no other choices. If we can give these kids choices, this community would be very different,” Aragones said.