The partition of Pakistan from India in 1947 created an independent state self-governed by the Muslims who formed the majority in the now-amalgamated regions. Of that population, the overwhelming majority of Muslims in Pakistan belong to the Sunni sect, with some estimates at more than 82 per cent.

The Ahmadiyya Muslim community is one of the Muslim minority groups in Pakistan who have faced challenges and been persecuted over decades.

An estimated four per cent of Pakistan’s population consists of religious minorities, including a number of Ahmadis who “continue to be relegated to the status of second-class citizens, vulnerable to inherent discriminatory practices, forced conversions, and faith-based violence,” according to an article by Vatican News.

The second amendment was passed in 1974 by the Parliament of Pakistan, declaring Ahmadis as non-Muslims, and since then, the community has faced repeated attacks, spurred by influential Sunni leaders. At times, Ahmadis need to conceal their identities for the safety of their families.

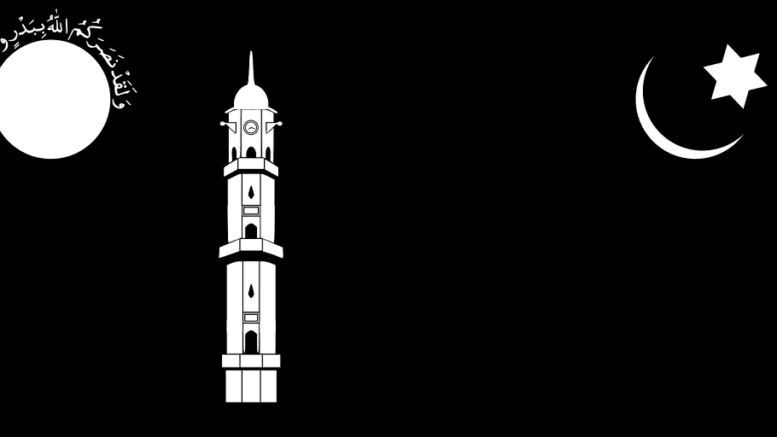

The Ahmadiyya Muslim movement began in the 19th century by Hadhrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, whom Ahmadis believe is the Promised Messiah. It consists of the members who follow the Ahmadi sect. Ahmadi mosques and communities are spread out in various countries, and members connect through weekly sermons delivered by global leader and Caliph, Hadhrat Mirza Masroor Ahmad.

Ahmadi members believe in a universal motto, “Love for all, hatred for none.” Despite the attacks that target the community, most Ahmadis prefer not to escalate or retaliate. Their faith dictates they should strive to resist conflict and preserve their peace.

The Toronto Observer spoke to two Ahmadis who say they migrated from Pakistan to Canada after facing great — and life-threatening — ordeals. One is a high-profile businessman added to a hit-list, and the other is a young woman who lost her father when she was a teenager; both are now Canadian citizens living in the Greater Toronto Area who can speak freely about what they experienced.

They share how their community was alienated in Pakistan, as well as the identity crises they endured while growing up.

Muzaffar Sheikh: I was targeted by radicals

“Being an Ahmadi poses so many restrictions that it’s incomprehensible for somebody to live there and not suffocate. The government legalized all ways to capitulate and break the community,” said Muzaffar Sheikh, a Pakistani Ahmadi who now lives in Vaughan, ON.

Sheikh, 41, father of five kids, said he is a survivor of religious persecution in Pakistan. Sheikh grew up in Pakistan’s third largest City, Faisalabad. He belongs to an affluent, family line of Ahmadis who built prestigious recognitions for themselves. Both of his parents were well-known Ahmadis, and were active in their local mosque.

Over time, his status as an Ahmadi Muslim put him on a radical group’s hit-list, Sheikh said.

He shared one instance when he saw his late father arrested for wearing an Islamic badge of the Kalima on his arm. Kalima is known as the first pillar of Islam, which Muslims declare their faith in two short sentences.

This was seen as an offence under “Zia-ul-Haq,” a blasphemy law that marks Ahmadis as non-Muslims. In another instance, a close family member was kidnapped by extremists for ten days, Sheikh said. His family was blackmailed into giving ransom money for his cousin’s life.

“After the incident, our freedom was curved. Every time we got into the car it was an ordeal, me and my family were always worried about someone stopping and firing at us. So then, we hired security everywhere we travelled. In that sense, you deprive yourself of having a normal life,” said Sheikh.

In 2010, Sheikh’s wife, along with her brother and father, survived the Lahore Model Town mosque massacre. Ninety-four people were killed that day, including members of her extended family. Sheikh said it left her scarred and in a state of trauma.

“There was no empathy felt by the wider community nor the administration. The sad part is they (media) phrased it as the ‘Ahmadi place of worship was attacked.’ Why was it not called a mosque? They were more worried about being politically correct than being sympathetic for what happened to our community.”

Sheikh’s family migrated to Canada shortly after.

A ‘vulnerable’ time for Uroosa after her father was martyred in Pakistan

Uroosa, an Ahmadi university student in Toronto who did not want her last name published for privacy and safety reasons, shared the experience of losing her father. Uroosa’s father was killed in Pakistan in the summer of 2013, at the age of 48. A colleague who was in the car that day survived.

“From what I know, there were threats, but my father didn’t tell us,” Uroosa said. “It happened so unexpectedly, we didn’t know of anything going on. He was driving one day and saw a protest ahead, so he decided to take another route which was a narrower road.

“On the way there, two men on motorcycles who were targeting him, followed his car, surrounded both sides and fired at him.”

“We were very vulnerable,” Uroosa said.

The next few years were a challenging period for her family. Uroosa’s mother had the responsibility of taking care of three young kids alone. While there were a few people from the community who came to help, most people kept a distance after learning the family’s Ahmadi identity, she said. As Uroosa grew up, she became more aware of the discrimination she faced.

“I strongly feel that even if you’re not living in Pakistan, the persecution, the opposition and the mindset is still the same. It continues on. This is not about changing countries, it’s about changing mindsets,” she said.

The immigration process to Canada took five years. Uroosa’s family arrived in 2018. Her mother resumed her studies and now works as a special-needs early-childhood education assistant.

Through the protection of diverse faiths that co-exist within Canada, Uroosa said she finds a sense of strength as an Ahmadi woman.

“Living in a western and progressive country, we should deeply educate ourselves of our roots so that we can educate people who persecute the Ahmadi community. We should befriend other Ahmadis because on a religious level, we can understand each other.”

Freedom in Canada as an Ahmadi Muslim

Uroosa said she hopes to be a supporting platform for other Ahmadi girls who have experienced religious oppression in Pakistan. She wants to start a campaign one day to educate her Canadian peers about the Ahmadi movement.

Muzaffar Sheikh said his experience in Canada has been liberating. In getting to know other Canadians, it strengthened him to be forthright in his beliefs and identity.

“Since the day I landed, from the first person I met, everybody was so welcome and sympathetic to the situation,” said Sheikh. “In the last 11 years, I’ve become a part of the system, I’ve grown here and I have a thriving business.”

Most importantly, he doesn’t have to hide his Ahmadi faith. “I can take my family to the mosque to pray and not be worried about being put in jail.

“It’s as if someone has choked you and that choke loosens, and you learn how to breathe properly.”

“It’s very heartbreaking. I still love Pakistan. I wish that country had a better constitution that would uphold the values like the ones in Canada,” Sheikh said.