It all came out at dinner one night.

We dine together every evening. My brother, mother, grandparents and I.

This time my brother complained about the dinner we were having and said he preferred something else.

“You are so ungrateful!” my grandfather said, as he often did when we complained about things that today I can’t even remember.

“I had to sneak food from Nazis when I was a child!” he would continue. “And you want to complain about food?”

He would often talk about how we should be thankful for the food we ate and how other parts of our lives, like going to school, were privileges.

We would usually brush it off and joke about how it was such an old person thing to say.

But this time was different, as it led to him telling us his whole story during the Second World War.

Barred in part of their home

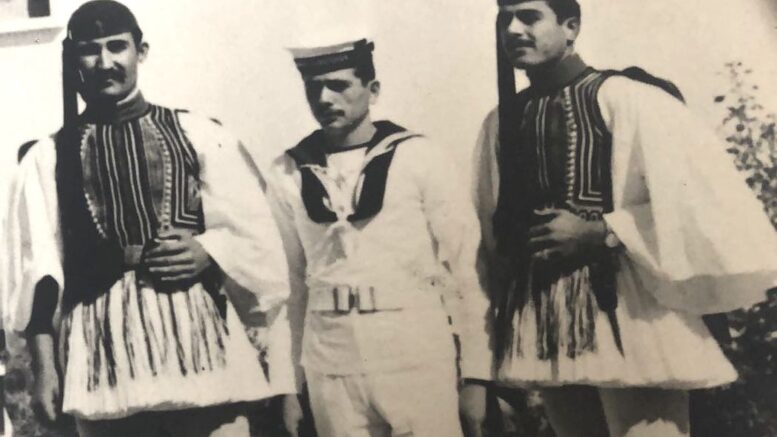

George Tsouroupakis, my grandfather, was born in Greece in 1934. He was the youngest of four siblings and the only boy.

He was seven when the German army occupied Greece, starting with the invasion from April 6 to April 30, 1941. Nazi soldiers put bars in his house to limit where his family could go in their own home. His mother would send him through those bars to carefully steal food while his older sisters paced the street to watch in case the soldier came back early. They weren’t allowed to speak too loudly, eat enough to sustain themselves, or live ordinarily in the place they were supposed to feel safest.

“One time, the soldiers were coming back early and [his sister] Cleo had run back to tell me and I dropped the bread all over the floor,” he said. “I remember crying, and my mother yelling at me to clean up the crumbs because if they knew we were on their side [of the house], something bad would happen.”

Costas Ioanndis, a Greek historian working for the Cretan Association of Toronto, teaching third and fourth-generation Greeks our history appreciates my grandfather’s story.

“It is important for the children [today] to understand how lucky they are to be living this life,” Ioanndis says. “It is important to know where you come from and to be proud of it.”

One of the most talked-about conflicts that Ioanndis teaches is the Battle of Crete, which took place about a month after the invasion of Greece. Crete is the biggest island of Greece, but furthest from the main land. My grandfather also talks about it all the time. The Germans sent many airborne soldiers to capture Crete because the Greek military wouldn’t be able to reach Crete to aid them before they got there.

“But after just a day of fighting, we sent them packing and wounded,” says Ioanndis, a Cretan native himself.

The Cretans fought with whatever they had—a few hunting guns and farming tools—and somehow sent the Germans back with heavy casualties.

“It is important for the children to know how important these times were to their own families, so that they may understand,” Ioanndis says.

My grandfather’s family also lived through the earlier occupation of Greece by the Italian army. Oxi Day, or The Day of No, is celebrated by Greeks worldwide on Oct. 28 as the day in 1940 when the Greek general and prime minister Ioannis Metaxas rejected an ultimatum from Benito Mussolini, founder of Italy’s National Fascist Party. Because of Greece’s proximity to Italy, Mussolini wanted to use the country to set up camps there due to Greece’s geographic location. Mussolini gave Greece an ultimatum to surrender peacefully. Metaxas told him “oxi” or no. It gave the rest of the world hope to know that a minor power like Greece was brave enough to stand up to the enemy.

Living through the occupation was completely different from everything my grandfather knew. Children couldn’t run around and play in the park like they used to, he remembered. Citizens would get in trouble due to the slightest missteps. People were disappearing.

“A boy had cursed at a soldier one day after school,” my grandfather said. “They said they were going to take him to the principal to be disciplined. We never saw him again.”

My grandfather’s father was a soldier at this time, so he wasn’t home. It was up to his mother to protect her children. One soldier occupying the home was kind to them. He and my great-grandmother developed a comradery throughout their time in their home. He was the youngest out of the party and would sneak the family food and extra water when he could.

Years later, when my grandfather moved to Canada and his nephew was the home’s caretaker, an older man and his son ventured down the driveway. They approached my uncle, asking for my grandfather and his sisters by name, wanting to know if they were around and if they were still alive.

The son explained to my uncle that his father used to be a soldier and lived in their house. He was the soldier who had helped my grandfather’s family.

“He came back that summer when we went to visit. We had him over for dinner and I was showing him the property. Yiayia was crying,” he said pointing to my grandmother. “She was thanking him for helping me.”

My grandfather watches the news frequently during this time of year, both Greek and Canadian sources. He watches anything and everything to do with the war and Remembrance Day so that he may reflect on those times and to be thankful for living through them. He reflects on how grateful he is for the life and family he has now, and those thoughts have transferred to me.

Now when I find it challenging to get up early in the morning or when I am not a fan of a particular meal, I am grateful I can live in a time where I can express those feelings.