Most mornings, 22-year-old student Naiza Limon (they/them) wakes up in pain. They get ready for their anthropology and sociology classes at Governor State University in Illinois and are extra careful not to let any of their belongings touch the floor, which to them is a source of contamination.

A few states south, Northern Texan Kenoya Musa (they/she) spends most days in bed, with their beloved service dog helping them navigate their hours awake. Musa has been in and out of work since 2020.

For a lot of people, the COVID-19 pandemic is a thing of the past. A few months of quarantine, a couple vaccine doses and a million masks later, everything went back to normal. The World Health Organization declared on May 5, 2023, that COVID is no longer a cause for international concern, effectively signalling the end of the pandemic era.

But for Limon and Musa, two disabled youth in their early 20s, long COVID is a daily fact of life.

“I’ve been disabled for at least a decade,” Limon said. “But it’s different now. Everything’s just a little bit harder than it was before.”

As we settle into the 5th year of the COVID-19 pandemic, businesses, schools and care facilities in Canada continue to decrease or remove COVID precautions. This poses a danger to a significant number of people in Canada.

Disabled and immuno-compromised people have been pushed further into the margins since the pandemic began in 2020, with immense emphasis being placed on society returning to a state of “normalcy.”

As COVID currently stands as the third leading cause of death in both Canada and the United States, it is getting harder to separate “normalcy” from inaccessibility.

Read more from the Toronto Observer:

- Younger Canadians are less tolerant of COVID-19 lockdowns than older Canadians: poll

- How the COVID-19 pandemic pushed some mosques to modernize

- COVID-19 restrictions heavily affect current and future development, some athletes say

Dr. Jonathan Li, director of the Harvard/Brigham Virology Specialty Laboratory and the Harvard University Centre for AIDS Research Clinical Core explains immunocompromised experiences as a spectrum.

“It’s not a homogeneous population that can be easily studied because of the diversity of their illness,” he said.

Li’s lab produced a report on how persistent (or chronic) COVID behaves in immunocompromised patients in January 2024. It found that mildly and moderately immunocompromised patients have a difficult time fully recovering from COVID. According to the study, severely immunocompromised patients have the most difficult time recovering, and could be potential sources of COVID mutations. It’s believed to be the first report of its kind.

Limon said their experience of disability is primarily with fibromyalgia, the main source of their chronic pain, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), digestive issues and a collection of other mental disorders. Musa said she experiences a similar multiplicity of experiences, including dissociation, chronic fatigue, panic disorder and other mental disorders.

Both came to the realization that they had developed long COVID within the last year.

Long COVID is a phenomenon in which symptoms of COVID 19 continue to occur even after recovery. The most common of which, according to the CDC, are chronic fatigue, shortness of breath, changes in smell or taste and muscle pain.

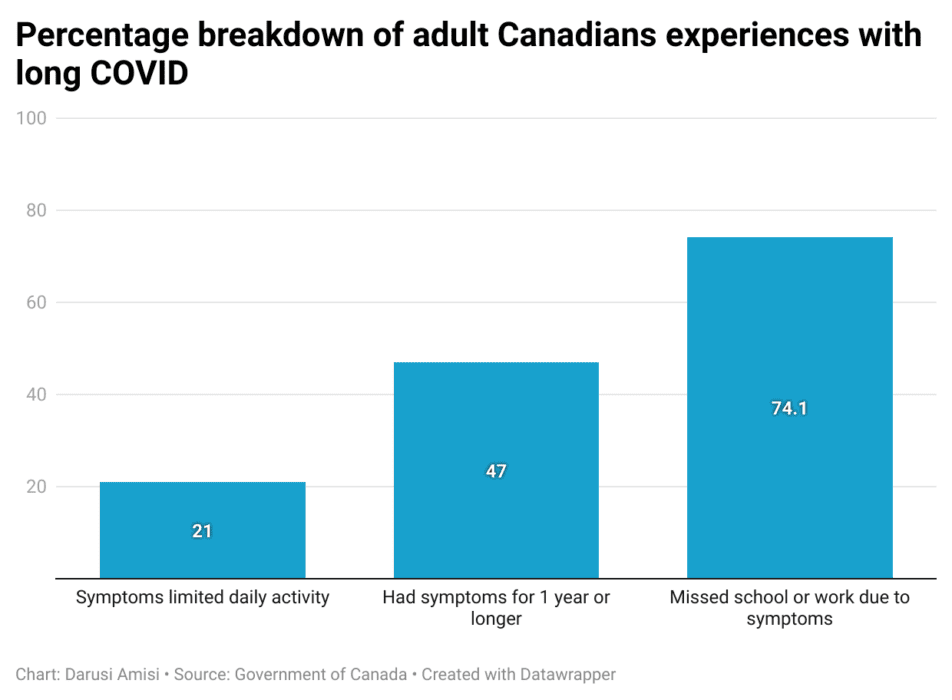

More than two million adult Canadians continue to suffer from long COVID symptoms, with 100,000 being unable to continue working or studying due to this, according to the Government of Canada. The decrease in public mask mandates and social distancing procedures continues to make more spaces un-accommodating, and sometimes dangerous for the disabled population.

According to Statistics Canada, long COVID has the potential to become a “mass disabling event” if not adequately addressed.

“While most of the world has returned to a normal life, it’s really the immunocompromised patients that oftentimes feel left behind,” Li said.

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted safety practices like masking and social distancing that are commonplace in disability culture. The pandemic helped make public spaces more safe and accessible for a lot of disabled and immuno-compromised people.

However, this type of protection has not always been the norm, and is slowly disappearing as institutions continue to abandon COVID restrictions.

Disability during the pandemic

The precautions that were put in place over the duration of the pandemic displayed the inclusive nature of disabled culture in its quest for public safety. Mask mandates, in place in Ontario from October 2020 to March 2022, decreased the transmission of airborne viruses. For many, the use of air ventilators led to an increased sense of safety sharing public space with others.

“A lot of jobs we realized didn’t need to be in office,” Musa said. “And then they all went back into office, which reduces options for people like me.”

However, as mask mandates became less and less compulsory, and we started to switch back to in-person work and gatherings, disabled people grew more and more isolated in their pandemic reality.

“It just makes me really angry and it makes me really upset,” Limon said. “The world has moved on as if COVID isn’t a problem anymore.”

“As if it doesn’t disable people. As if it doesn’t kill people.”

—Naiza Limon, a person living with long COVID

Li’s team at Harvard/Brigham Virology Specialty Laboratory were one of the first to discover that SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID, can be found in the bloodstream. More recently, scientists at the University of California San Francisco found that COVID antigens could remain in the body for up to two years after first contracting the disease.

“I feel like a lot of the research and the science that we do know has been ignored so that everybody can ‘return to normal’,” Limon said as they explained the frustration and isolation they feel in often being the only one in the room still practising COVID precautions.

Musa expressed a similar feeling of frustration, saying that they “think people were sick of all the restrictions.” However, they are still perplexed at the loosening of COVID restrictions.

“Even if we feel like the virus is over, why are we not ventilating? Why are we not sanitizing things?”

—Kenoya Musa, a person living with long COVID

The remnants of the socially recognized pandemic era haunt the walls and floors of supermarkets, government buildings and doctor’s offices as social distancing stickers and mask requirement signs. This can create a false sense of security for the people who still depend on those precautions for their well-being.

“For a disabled person to be at the door and say, ‘Oh okay! I’ll be safe here’ and then walk inside and it’s completely different is “just really disheartening,” Limon said.

Long COVID and intersectionality

Since developing long COVID, both Musa and Limon’s existing disabilities and symptoms have been exacerbated by the disease.

“Personally, especially as my disabilities have worsened,” Musa said. “I feel like I’ve been kind of abandoned by society.” Before the pandemic, Musa used to work as a personal trainer, something that long COVID symptoms like shortness of breath, dizzy spells and chronic fatigue prevented them from pursuing following their development.

Similarly, Limon doesn’t feel that their health ever returned to its baseline before they contracted COVID.

“I’m here three years later and I still use the same perfume that I used before my first infection because I know I liked the way it smelled when my (sense of) smell was normal,” Limon said.

Both Limon and Musa believe their experiences were influenced by their existence as racialized queer people. The experiences of disabled people with further marginalized identities are different from those without intersecting identities, contributing to the spectrum of experiences within the disabled community.

“If you add in other things like class, race, gender, sexuality, there’s even more marginalization within that,” Limon explained., “In a lot of ways, our voices are suppressed.”

Musa, who navigates the world as a Black woman, detailed some of their experiences with medical racism, stating that she “was never taken seriously in the first place.”

“When I’m incapable of certain things, people use it to confirm biases about me,” they explain further.

WATCH | Looking to the future:

Several medical institutions such as the Canadian COVID Society and Public Health Ontario recommend that the best way to prevent the development of long or chronic COVID is to take the prevention measures to avoid contracting COVID in the first place.

This means staying home when you’re feeling unwell if you’re able to, wearing a mask or face covering, and prioritizing indoor aeration and ventilation.

“I wish masking wasn’t so ridiculous socially,” Musa said.

Limon emphasizes that they are “crucial to my protection, to protecting those around me as well.”

One thing that we can learn from the disabled community going forward is this: the COVID pandemic didn’t end in 2020.