In folklore of the Onkwehonwe, there was a tumultuous era long ago known as the Dark Times, where warring Indigenous nations were driven by anger, revenge, fear and jealousy causing destruction and ruin. Amid this darkness, the Creator sent a messenger they call the Peace Maker, who brought the Mohawk, Seneca, Cayuga, Oneida and Onondaga nations together as the The League of Five Nations under what’s called the Great Law of Peace. The nations refer to themselves as the Onkwehonwe, or “The Original People.”

This wisdom of peace produced the first covenant, the One Dish, as the Onkwehonwe emerged from the Dark Times into the light. It was “an agreement by all the leaders to see all this land as one dish that nourishes us all, and helps us all to be healthy, and survive, and look after our future generations,” said Thohahoken, 70. A descendent of Mohawk leader Joseph Brant, he is an associate professor at Toronto Metropolitan University also known as Michael Doxtater.

That agreement is passed down to younger generations by elders through intricate storytelling and the metaphor of a solar eclipse, Thohahoken said.

On April 8, as North America prepares to witness a total eclipse of the sun, Thohahoken will be speaking at the Mohawk Institute, one of Canada’s longest-running residential schools. His community will be looking to the sky to commemorate their Indigenous perspectives on the cosmos.

The descent into complete darkness in the middle of the afternoon will be meaningful for them, and perhaps to all of us. An estimated 31.6 million people in Canada, the United States and Mexico will experience complete darkness during the day — up to four and a half minutes for those in the centre of the path.

WATCH | Thohahoken explains the significance of eclipses in Indigenous folklore:

With April 8 just around the corner, read along to find out why some people consider cosmic events so spectacular.

What is a solar eclipse and how do we know when one will happen?

A solar eclipse happens when the moon passes between the sun and Earth. The alignment blocks the face of the sun and casts a shadow on Earth. This phenomenon leads to either partial or total darkness for a few minutes depending on the observer’s geographic location. The precise alignment of these three celestial bodies is known as syzygy.

Astronomers in the ancient civilization of Babylon studied when lunar and solar eclipses would occur using the Saros Cycle, a period they observed to be 18 years and 11 days long, or 6,585 days. This interval is when the sun, the moon and Earth realign to relatively the same positions. The last total solar eclipse in North America took place on Aug. 21, 2017, but was only visible as a partial eclipse from Canada.

These days, scientists are able to predict exactly when and where eclipses will occur using advanced computational programs. For amateur enthusiasts of astronomy, a free open-source software known as Stellarium is available online. It allows users to track forthcoming eclipses and learn about stars and constellations.

What sets this eclipse apart?

During this eclipse, it will be possible to watch the sun disappear behind the moon — the path of totality — in some parts of Ontario.

“This eclipse is spectacular because of the number of people that get to see it and the amount of time that we have for totality,” said Elaina Hyde, a professor of physics and astronomy at York University.

“In Ontario, we will not get another chance of a total eclipse like this for well over 100 years.”

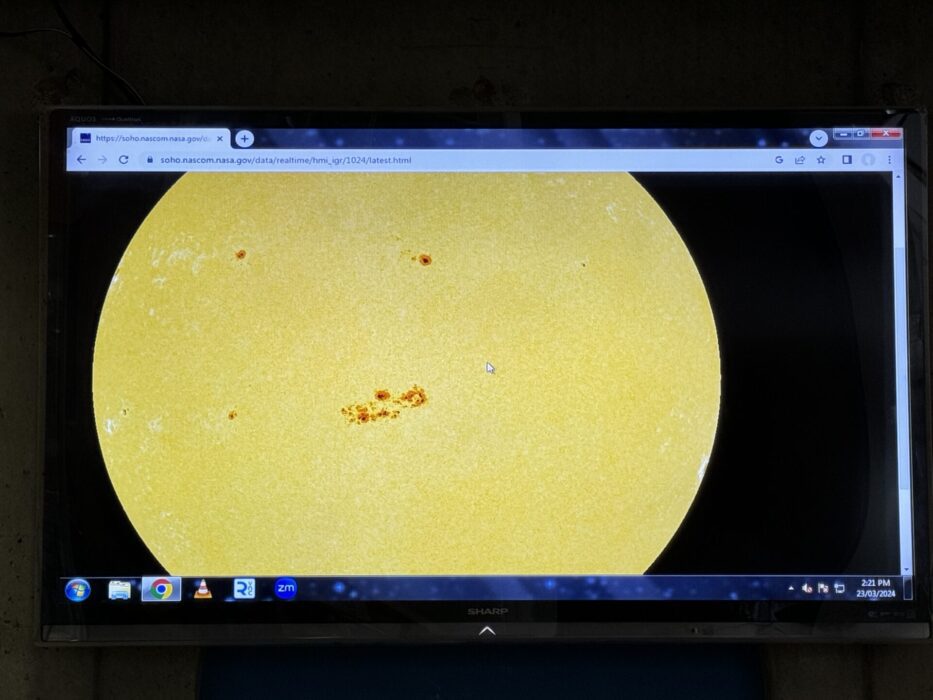

Another notable contrast between this eclipse and the one in 2017 lies in the sun’s activity, which increases and decreases every 11 years as part of the regular solar cycle. According to Hyde, who is also director of York’s Allan I. Carswell Astronomical Observatory in Toronto, we are approaching maximum solar activity, resulting in the formation of the maximum number of sunspots — areas of magnetic activity on the sun that people might be able to see.

Only the largest sunspots can be seen, and they will show up as tiny little dots. They are “quite fun and it’s a whole extra thing of solar observing that everybody can enjoy,” said Hyde.

How to view this eclipse safely

Hyde wants to ensure everyone watches the eclipse safely.

That means you shouldn’t look directly at the sun unless you’re wearing special glasses. Only ISO-rated solar viewers are safe for viewing the eclipse. Regular sunglasses do not block out enough of the sun’s damaging rays. When solar viewers are correctly worn, you cannot see anything around you. When you turn to face the sun, only the sun will be visible.

WATCH | Observatory director explains how to use solar viewers properly:

As the eclipse begins, the sun will appear as a crescent through the solar viewers, until the crescent disappears and the sky darkens, at which time it is safe to remove the solar viewers. As soon as the sun starts reappearing, put the solar viewers back on if you plan to look up and observe the eclipse again.

Hyde also offered advice to amateur photographers trying to capture the eclipse.

“One thing I will caution people about if you have these kinds of glasses, you would be tempted to try to get a picture of the sun. So put [the solar viewer] over your phone camera.”

Like our eyes, the sensors in phones and digital cameras are highly sensitive and prone to damage from direct exposure to the sun.

The next exciting celestial event taking place

April offers more than just this eclipse. The Comet 12P/Pons-Brooks will make its closest approach to the solar system around April 21 as part of its 71-year orbital cycle. During peak visibility, the comet can be seen streaking across the sky by the naked eye.

For those eager to deepen their understanding of the cosmos, AICO hosts public outreach events such as viewing sessions and group tours. The observatory is open for in-person viewing every Wednesday evening after sunset. It boasts the largest telescope on any university campus in Canada — a 60-centimetre Cassegrain.

WATCH | Fuel your cosmic curiosity at the Allan I. Carswell Astronomical Observatory:

Just as ancient Babylonian astronomers painstakingly recorded each eclipse on clay tablets across centuries, scholars at AICO continue the pursuit of unraveling celestial mysteries, as the rhythm of time brings humanity a deeper understanding of our universe.

For Thohahoken, April 8 signifies “people coming together.”

Like the Indigenous who view the eclipse as a transformational event with peace as its central message, perhaps it will also serve to remind others of our interconnectedness on Earth.

WATCH | Learn more about the Dark Times and solar eclipses in Indigenous folklore: