Roughly a year from now, Pape Village will be enveloped in construction and development to make way for the long-awaited Ontario Line, notably on Pape Avenue — the backbone of Greektown.

The largest, most costly planned development to be added to the Greater Toronto Area’s (GTA) transit system is poised to be life-changing for Torontonians who continuously hope for better reliability and efficiency in commuting throughout the city.

“What it does that’s really important is it creates new connection points. It actually makes our network more complex, which means it makes our network more resilient,” said Cameron MacLeod, executive director of CodeRedTO, a volunteer-led transit advocacy group for the Greater Toronto and Hamilton Area (GTHA).

“If something breaks, people can get around that breakage more easily because there will be new ways to connect and travel around the system.”

Since the project’s unveiling headed by Premier Doug Ford’s government in 2019, the budget needed for it to materialize has more than doubled from the initial $10.9-billion allocation, according to Metrolinx, the Greater Toronto Transportation Authority and an agency of the Government of Ontario. Ever since the project’s announcement, neighbourhoods across the city have taken action to raise awareness for the safety and wellbeing of their communities, and Pape residents have been doing exactly that.

“The idea of more network growth and network complexity is very important. What’s also important is strong, predictable operations funding,” MacLeod said.

“The Ontario Line is not gonna make money. Transit doesn’t make money. The Ontario Line is going to cost money.”

Watch: Experts and advocates discuss the Ontario Line:

What is the Ontario Line going to look like?

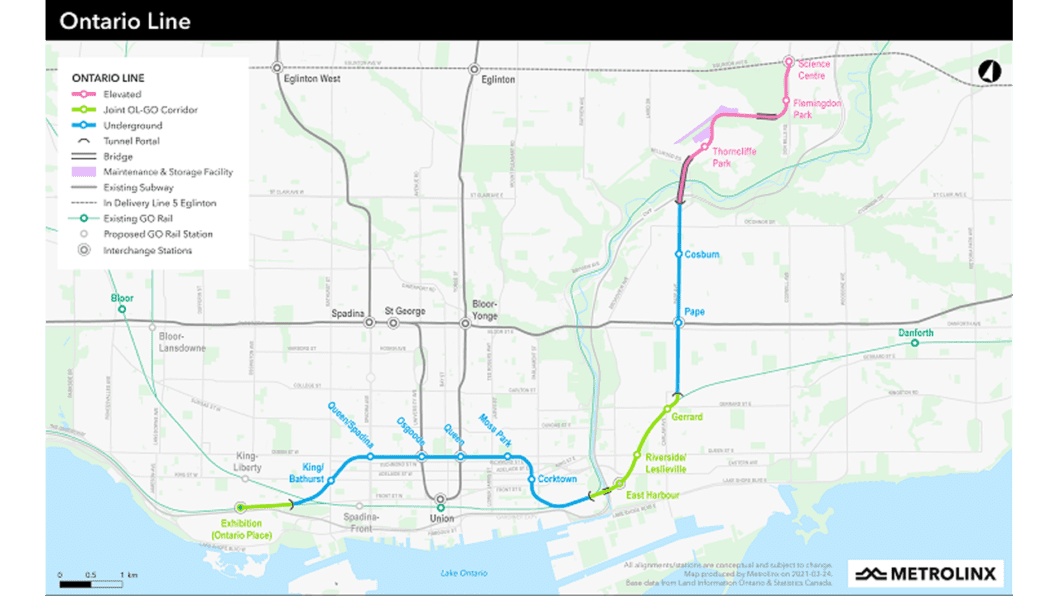

Construction for the new line broke ground in December of last year, kicking off an estimated decade-long construction timeline for a 15.6-kilometre end-product spanning west from Exhibition Loop, through the downtown core, connecting east at Pape Avenue and stretching up to the Ontario Science Centre. A total of 15 stations and more than 40 transit connections is nothing less of a growth spurt for the future of the city’s public transit network.

According to MacLeod, this is what this city continues to struggle with.

“One thing that this city has a really hard time with, this province, this country and this continent has a big problem with is the idea of prioritizing the movement of people over the movement of cars,” he said.

Lanrick Bennett Jr., a Greektown resident and executive director of The Laneway Project, a non-profit social organization dedicated to helping communities develop laneways and public spaces, agreed.

“We need a robust public transit system that is timely, that is safe, of course, but that it gets you places — that’s how you beat owning, or at least depending on a car,” he said.

Before it was the Ontario Line, it was the long-expected Relief Line

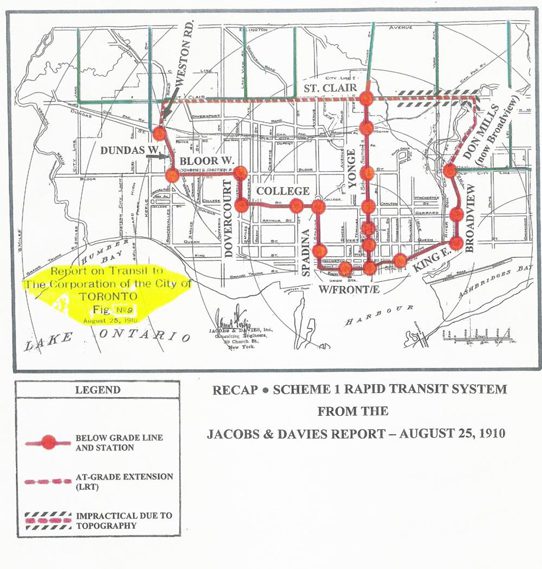

The envisioned Ontario Line did not always look like this; instead, it has become a culmination of plans, changes and delays that go as far back as a century — when the original plan for the Relief Line was born.

“This is something that has been needed for decades, it’s something that’s been talked about for literally more than a hundred years,” said MacLeod.

“The Relief Line idea has shown up on maps of downtown Toronto from 1910. It’s something that was always part of future planning.”

Bringing relief to an existing transit line comes from the need to magnify where passenger traffic is the busiest and establishing new connections to split up the density of passengers passing through a station. We see the melting pot of this density emanate from the downtown core, specifically the Bloor-Yonge subway station that houses interchanges for Line 1 and Line 2 on the Toronto Transit Commission (TTC) subway network.

According to statistics available from the TTC, in 2019, Line 1 averaged a daily weekday ridership exceeding 825,000 commuters and heralding it as one of the busiest transit lines in North America. A big flaw in the current subway system is that in order for commuters to reach the east or west ends of the city via a rapid line from either the city centre, north or south, more often than not it becomes necessary to pass through Bloor-Yonge station interchanging between Lines 1 and 2.

“That’s one of our biggest challenges within our existing subway system — we have enough capacity for everybody, but we don’t have enough capacity for everybody in the right places,” said MacLeod.

Pape’s vital role in bringing relief goes way back, but for now and in the future, at what cost?

During the route planning for the former Downtown Relief Line back in 2016, Pape was planned to be a terminus station under the former line’s sub-phase previously dubbed the Relief Line South, with the other planned terminus station being Osgoode as part of the same objective to ease congestion from the Bloor-Yonge interchange.

The upcoming Ontario Line still has this same objective for including Pape station on its route. According to Metrolinx, this station will provide commuters an additional rapid option to get to downtown apart from the current lone route on Line 2. Through this, it aspires to alleviate overcrowding during rush hours at Bloor-Yonge station by 22 per cent, and the busiest section of Line 2 by 21 per cent.

However, residents throughout Toronto face years of their neighbourhoods being taken apart in life-changing ways before they can experience the benefits of an enhanced transit system. The area around Pape station is among them.

“The actual future users of the Ontario Line, they’re going to be hurt by the construction of the Ontario Line,” said MacLeod.

As construction works its way from west to east, the East York neighbourhood will find itself becoming more affected when construction is in full swing at the Pape and Cosburn stations, and up toward the proposed route in more or less a year from now. Short-term projects are already raising concern for residents.

On April 10, Metrolinx simultaneously began conducting three short-term developments as part of construction testing and preparation including:

- A hydrovac test pit along a laneway west of Pape Avenue and south of Cosburn Avenue

- Geotechnical drilling on Minton Place near Hopedale Avenue

- Investigative work at the intersection of Pape Avenue and Riverdale Avenue

After the Ontario government unveiled its plans to develop the Ontario Line in 2019, Pape Area Concerned Citizens for Transit (PACCT), a grassroots community organization, formed in response.

“Our neighbourhood is pro-transit. We want more transit in Toronto. We just want better planned transit and smarter transit. Not rushed transit plans that would have long-term negative impacts,” said Richard Sigesmund, a member of PACCT’s executive committee.

“Our goal is to try to work with them and to ensure that our concerns are heard and addressed.”

The organization’s biggest concern is advocating for reassessment in Metrolinx’s proposed plan to build a tunnel north of the Pape and Cosburn stations that would emerge at Minton Place, a street that continues north when Pape Avenue bends northeast to meet Leaside Bridge.

“The problem is that as the subway line goes north from the Pape subway station, the line goes higher and higher, and closer to the surface,” he said. “In order to build a subway line, they’re going to have to put in a tunneling machine. Tunneling machine’s going to be operating 24/7 underneath people’s homes.”

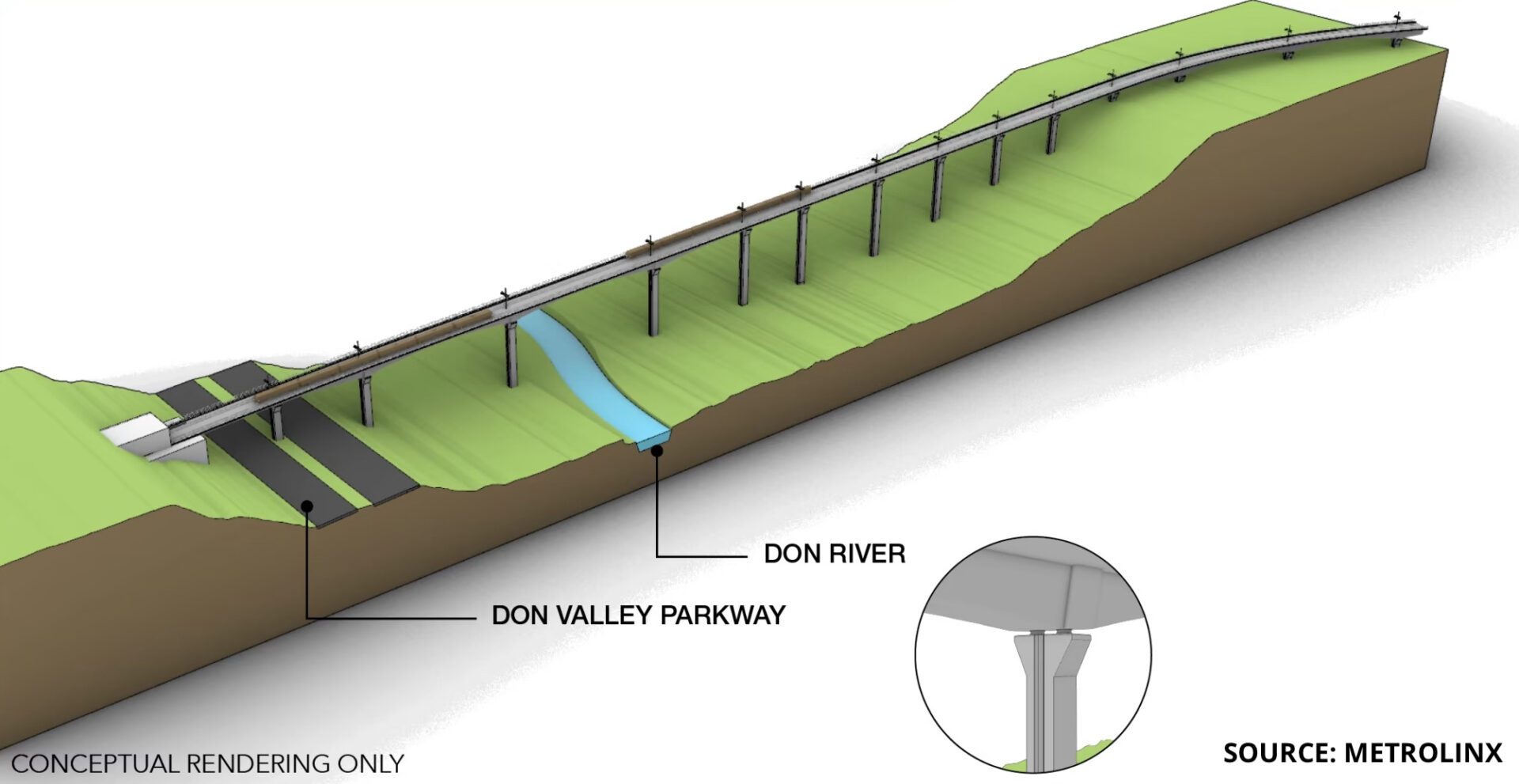

The end tunnel is designed to meet a new Don Valley crossing, a bridge that will connect the line north to a new Thorncliffe Park station. In order for Metrolinx to put the development of those structures into motion, it wants to expropriate four homes.

“This isn’t a case of us saying we don’t want a subway line and we don’t want it in our neighbourhood. We just look at this plan and we look at the negative impact on homes that have been here for over a hundred years,” said Sigesmund.

“It is literally going in the backyards of some of our neighbours, which could impact our neighbours’ safety; the pollution, the noise, the vibration impact of it.”

The impact of households being told that the homes they have built their lives in will be expropriated is unnerving. A year before shovels hit the ground can sound like a long time, but for those who face the uncertainty of completely uprooting their lives, the question is: Is this really worth it?

How could communication be better in highlighting the benefit and safety of residents?

In order to raise awareness and to proactively represent the community, PACCT continues to prioritize communicating the neighbourhood’s concerns directly to Metrolinx.

“We’re doing everything we can to stay as on top of the plans as we can, and to every step of the way address our concerns, and Metrolinx has heard our concerns,” said Sigesmund. “Our concerns are about that bridge in its current location and its negative health impacts that it could have in our neighbourhood — we hope and believe that a covered bridge would minimize some of the noise and vibration.”

Even with proposed transit growth that has long highlighted a sole objective of becoming beneficial to the lives of Torontonians, finding middle ground in communication has proven to be challenging.

“You can definitely feel the frustration of getting information and that not translating into exactly what could be coming forward,” said Bennett.

Bennett, who was appointed the first-ever Bicycle Mayor of Toronto, has long advocated the importance of bridging the gaps between city councillors and their communities that are affected by the construction of the Ontario Line. He has tried to help by previously communicating with Toronto-Danforth Coun. Paula Fletcher, who has been proactive in demanding transparency surrounding Metrolinx’s communication to the public and matters concerning her constituent’s safety.

“There needs to be a much better partnership through the Metrolinx entity and our councillors so that information gets to residents in a timely fashion, and so that they feel that they’re engaged and being a part of what’s being put forward,” he said.

Transit that increases the quality of life, but hopefully not reduced in order to build it

It’s compelling to sit and think about the benefits the Ontario Line could prove to boast in a decade or so from now if you’re able to look past the growing pains of what is being compromised to get there. Knowing that the essence of transit is utilitarian in nature, seeking to benefit the most people at once over the dependence of private vehicles.

“I need to know that I can go from home to work, to school, to play — to all of these things — without my vehicle,” said Bennett. “We haven’t given users enough confidence that their public transit system can do that, hoping that a project as large and as robust as the Ontario Line really does spark that commitment again.”

Metrolinx has proven it’s adamant to reach its end goal with construction development well underway, but with anything that seeks a significant impact, comes a balancing act of the net positives with net negatives and these continue to be concerns that people hope will not be overlooked.

“We know that there’s aches and pains, growing pains of building a subway line, we’re realistic about that happening,” said Sigesmund.

“This is not how you bake a proper cake. This is how you rush baking a cake and you get bad results and we don’t want that.”

Read more from the Toronto Observer: